Lesley's Blog

This is the blog of Lesley Broster Kinch, author of The Love of Money and The Root of all Evil. Both novels are set in 17th Century New Amsterdam, which back then was a trading out-post that was eventually to become what we now know as Manhattan - The financial capital of the world.

To research her novels, Lesley has been delving in the history books and this blog is her observations of revelations that she has unearthed - a literary equivalent of peering behind the scenes stage of a play!

WHY DID THE PURITANS FLEE ENGLAND IN 1620?

English King, Henry the Eighth, wanted a divorce from his first wife Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry his new love. As this was a Catholic marriage, he was refused an annulment from the Pope. To get around this obstacle he decided that he would repudiate Papal Authority and transform the Church of Rome to the state Church of England. Henry got his divorce and then married Anne Boleyn.

This rather blatant act of personal selfishness set in motion an upheaval of religious and social order that would last for centuries.

Many worshippers who had initially welcomed the break with Catholic church and its excesses began to become disenfranchised with the Anglican Church as it still retained many similarities to the Church of Rome.

The PURITANS (sometimes known as the ‘precisionists’) were one such group who wished to see the purification of the Anglican Church of all remaining Catholic rituals and liturgy.

Those wishing a complete break with the existing church became known as the SEPARATISTS.

The King decreed that all citizens were to follow the state religion ie the Anglican Church.

By 1603, when James 1 ascended to the throne, the situation had become perilous for those seeking religious freedom.

The Separatists, mainly from northern England, found life in England untenable and decided to flee the kingdom in pursuit of religious freedom. After several abortive attempts to leave England, they finally arrived in the Netherlands in 1608. William Brewster, who had founded the Scrooby Separatist Church in his home, Scrooby Manor was joined by William Bradford, who was to later write a diary of the group's story in his book, Of Plimoth Plantation.

The Separatists settled and practised their form of worship in the forward-thinking City of Leiden in the Netherlands. They worked, mostly in the flourishing textile industry, and their children were baptised in the Pieterskerk, the Hooglandse Kerk or the Vrouwekerk.

The reality of their new life soon began to give cause for concern. They were not permitted their own place of worship. Leiden was a bustling University city and was incompatible with the rural upbringing of the Separatists. They were also afraid that the Dutch way of life was influencing their children and that they would eventually become divorced from the English way of life.

Therefore the decision was made, in conjunction with a fellow congregation in England, to travel to Virginia in New England. In order to raise the money needed for such a journey they secured a deal with the Virginia Company, which was actively seeking colonists to settle in New England. The Separatists would work for them to repay that investment. The ship The Speedwell was purchased for the journey. In August 1620 they left Delfshaven to rendez-vous with The Mayflower.

The Puritans, however, who were not strapped for cash, saw the journey to the New World as an ideal investment opportunity to own land and create their ideal English Church away from English religious persecution.

On July 20th 1620, The Mayflower left London's docklands with approximately 65 passengers and 30 crew members. The ship was a three-masted, four decked Dutch cargo Fluyt 80-90 feet in length on deck and 100-110 foot overall. Her stern carried a 30 foot high aft-castle that made the ship unwieldy and difficult to sail close to the wind and was totally unsuited to the North Atlantic’s prevailing westerlies especially in the autumn/winter months.

The English Puritans, who were to become known as the Pilgrims Group from around 1800, were packed in close confines on the gun deck, a space measuring 50 feet by 25 feet. In the cargo hold beneath the gun deck all the passengers' food stores, clothing, weapons and utensils needed for a new life were stored. They did not have toilet facilities. The privy was a bucket fixed to the main deck or bulkhead for stability. Access to the main deck above was through gratings using a wooden or rope ladder.

The Mayflower proceeded down the River Thames and into the English Channel. She sailed along the southern coast of England to moor at Southampton Water and to await the arrival of The Speedwell.

Read the first 50 pages of Lesley's novel for free

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

A Homage to Independence Day USA

And the curious case of two deaths*

Throughout the many years of research for my book, The Love of Money, I was constantly struck by historically documented tales of the tenacity and ingenuity of the European settlers who colonized the East Coast of America and how that spirit to survive and flourish in a hostile New World imbued their descendants with a steely determination to rid themselves of foreign tyranny and injustice.

In Philadelphia on January 10th, 1776, a fellow countryman of mine published an anonymous pamphlet. It was tantamount to a treasonable act at the time as it called for Americans to rise up against the oppression of the British King George and his punitive laws and taxations. Its working title had been Plain Truth, but its published name was Common Sense and it was written by Englishman, Thomas Paine. It achieved extraordinary sales reaching most of America's then 2.5 million colonists. Paine maintained his anonymity until March 30th, 1776. He donated all his royalties from Common Sense to George Washington's Continental Army.

The sentiments and passion in the pamphlet captured the hearts and imaginations of a newly cohesive people and inspired the Thirteen Colonies to declare their position and fight for independence in

the Summer of 1776.

On July 4th, 1776, the Continental Congress approved Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence from Great Britain. This day was described by John Adams as 'the most memorable epoch in the

history of America.'

Adams also stated that this first day of debate of this Declaration 'will be forever celebrated in America.' 'It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God

Almighty,' he wrote. 'It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illumination, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time

forward, forevermore.'

His prediction could not have been more accurate.

John Hancock, President of the Congress, declared after scrawling his signature rather boldly across the document, 'There, I guess King George will be able to read that.'

Ben Franklin reflected, with a shot of humour, that, 'Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.'

On September 9th, 1776, the nation's name changed from the United Congress to the United States.

* The two, and possibly, three, extraordinary deaths on Independence Day, July 4th.

Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, aged 83 and John Adams of Massachusetts, aged 90 both died on the same day in the same year – July 4th 1826 – the 50th Anniversary of the signing of the declaration of

Independence. Eerily, five years later to the day, James Monroe, fifth US President, died aged 73.

Lastly, I would like to pay my respects to the bravery and courage of those Founding Fathers.

Read the first 50 pages of Lesley's novel for free

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Mother’s Day/Mothering Sunday

I’ve always wondered why the UK and USA had differing dates for celebrating the same day - Mother’s

Day.

The name itself is misleading. Mothering Sunday in the UK, now increasingly known as Mother’s Day, is a Christian holiday. Mother’s Day in USA is a secular

holiday.

The Christian holiday falls on the fourth Sunday, Laetare Sunday, exactly three weeks before Easter Day. From the 16th century The Roman Catholic Church, Church of England and Anglican

parishes

throughout the world would observe this day and parishioners would celebrate by visiting their mother church. One’s mother church was either where you were baptised or a church within your

parish.

Domestic staff were given the day off to visit their church along with their mothers. It has subsequently evolved into a day on which presents are given to the mothers of children to honour their

role in family life. Picking wildflowers en route to donate to the church later became the well-known tradition of giving flowers to all mothers on Mothering Sunday. Other names for the fourth Sunday

in Lent include Refreshment Sunday, Pudding Pie Sunday (in Surrey, England), Mid-Lent Sunday, Simnel Sunday and Rose Sunday.

Mother’s Day in the USA is a possessive phrase as it applies to a singular mother. This annual, secular holiday is celebrated on the second Sunday in May and was established by Anna Jarvis in

recognition of her mother’s attempts to set up a day, post Civil War, to favour peace and not war. Ann Jarvis set up a committee in 1868 to establish a “Mother’s Friendship Day”, whose aim was to

reunite all those families who had been torn apart by the Civil War. Several short-lived observances in New York, Boston and Protestant schools in the USA during the 1870’s and 1880’s, but none

achieved national status.

Sadly, Ann Jarvis died in 1905 before she was able to establish the National holiday. Her daughter, Anna, took up her cause and the first official Mother’s Day was celebrated on 10th May, 1908 at

St.Andrews Methodist Episcopal church in Grafton, West Virginia.

A proclamation by President Woodrow Wilson on 9th May 1914, resulted in establishment of the first national Mother’s Day. This is now held on the second Sunday in May. American citizens can show the

flag in honour of those mothers whose sons had died in war.

Traditions on Mother’s Day include churchgoing, gifts of bunches of carnations and family dinners. Carnations have come to represent Mother's Day since Anna Jarvis delivered 500 of them at the first

celebration in 1908 in honour of her mother’s favourite flower. Many religious services held later adopted the custom of giving away carnations. This also started the tradition of wearing a carnation

on Mother's Day. Partly due to a shortage of white carnations, and in part due to the efforts to expand the sales of more types of flowers in Mother's Day, florists invented the idea of wearing a

pink carnation if your mother was living, or a white one if she was dead.

Unfortunately, excessive commercialisation of the Mother’s Day began early on, and only nine years after the first official Mother's Day, it had become so unpalatable that Anna Jarvis herself became

a major opponent of what the holiday had become, spending all her inheritance and the rest of her life fighting what she saw as an abuse of the celebration.

Mother's Day is now one of the most commercially successful of all American national holidays. Spending for that one day on gifts reaches approximately $2.6 billion on flowers, $1.53 billion on

pampering gifts—like spa treatments—and another $68 million on greeting cards.

Read the first 50 pages of Lesley's novel for free

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

A Mother's Power

The responsibility that comes with becoming a mother is both frightening and exciting. I understand now that the reality of either loving your child or rejecting your child has far-reaching effects on them - it can mean the difference between them leading a happy, fulfilled life or one that is lived in constant self-denigration and unhappiness.

It is magical being a mother, but it was not something that was immediately obvious to me when I first became pregnant, nor throughout my pregnancy, nor during a scary, Cesarean-necessary birth.

My mother had told me when I was about five that she hadn't wanted me, didn't want me. I had ruined her whole life as she could no longer get a divorce from my father- at that time marriage was

inviolate! So I grew up knowing that my mother disliked and resented me: there were no kisses, no cuddles nor any show of care or love.

When I got married and became pregnant a year later, I had no notion of what being a mother meant, so I approached the whole thing in a cold, calculating frame of mind. I read everything there was to know about pregnancy - I had been a researcher with the Sunday Times Newspaper and so knew how to ferret out information. Gordon Bourne’s ‘Pregnancy’ was my bible. I was a well informed amateur which, it turned out, was quite useful when things went horribly wrong during the delivery. I had a pretty good idea about what the medical team was doing.

Returning home with my new baby, in considerable discomfort from my operation, I still had no particular bonds with my child. That is until a foolish midwife said something about my son and then I was a She-Devil from Hell! From deep within me came emotions I didn't think I was capable of producing - a burning, physical rage swept over my entire body, firing me to a height of anger I'd never felt before. At that same split second, I felt the most chest-swelling love for my little boy that still exists today, several decades later, and it is exactly the same with his younger brother.

Being a mother had opened up an unknown sentient dimension in me that, in turn, opened up love, empathy and an awareness of real life. Prior to this, I had enjoyed a life of fabulous jobs, holidays and a social life to die for - I wasn't shallow, just ignorant of a finer state of humanity.

I love my two sons passionately and I am so grateful that I experienced something that my poor, misguided mother couldn't - mother love.

Read the first 50 pages of Lesley's novel for free

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

History Repeats Itself

Pieter Stuyvesant

Governor Pieter Stuyvesant was an irascible, dictatorial tyrant who ruled over the Dutch colonial outpost of New Amsterdam, Manhattan Island. As Director General, Stuyvesant brooked no discussion or dissension from his citizenry nor the newly elected municipal government. He clapped his opposers in irons and banished them from the colony.

In response to a worsening situation between the Dutch and the English, the Dutch West India Company tasked Stuyvesant with the building of better defences for the town.

In 1653, a wall was built to protect New Amsterdam from the English who were at the time gathering warships in Boston Harbour readying to sail south and take the colony.

Stuyvesant had called on forty-three of the wealthiest citizens of New Amsterdam to fund the wall at a cost of 5,000 guilders which they did charging ten percent interest on the sum, the first

municipal debt of the town.

The wall stretched across the entire northern border of New Amsterdam with blockhouses at either end and gates added to routes into the town.

However, by the time the wall was completed the Dutch and the English had signed a peace treaty. The wall and the debt was no longer necessary.

The presence of the wall had very little effect on the historical outcome of New Amsterdam’s future - in 1664 the English took the town and renamed it New York.

That was three hundred and sixty three years ago in the face of an enemy intent on military and naval invasion. In the end a border wall across a stretch of land did nothing to protect it from

seaborne invasion.

If this seems like a familiar story of borders and wall building, then think again. Compare the threat faced by New Netherland colonists from an aggressive, land-grabbing foe like the English in 1653 to the mostly unarmed and peaceable immigrants seeking asylum in the United States.

Most of these settlers were fleeing from persecution, poverty and religious oppression in Europe.

te it.

Donald Trump

President Donald Trump is a third generation immigrant. His grandfather, as a matter of record, was a draft dodging German baker who emigrated illegally to the United States aged 16 yeas in October 1885.

At that time, Germans were seen as highly desirable migrants—and Trump was welcomed with open arms. Less than two weeks later, he arrived in New York, where he would eventually make a small fortune.

More than a century later, his grandson, Donald Trump, became the 45th president of Friedrich’s adopted home.

Sadly, President Trump denied this German heritage, claiming that his grandfather’s roots lay in Sweden.

Trump maintained the ruse at the request of his own realtor father, Fred Trump, who had obfuscated his German ancestry to avoid upsetting Jewish friends and clients.

Other notable US Presidents have underlined their term in office by supporting construction projects that enhanced the lives of its people. The transcontinental railroad was facilitated by Abraham Lincoln introducing legislation for land grants and financing, Theodore Roosevelt, the Panama Canal and Dwight Eisenhower, the Interstate Highway system.

Trump’s wall is not constructive, it is divisive: building barriers and walls between neighbouring countries and their peoples.

The United States of America was built on the backbone of immigration of European nationalities: English, Dutch, Swedish, German, French, Spanish, to name a few. The diversity of the American character comes from the strengths, traditions, religion and skills brought by these brave antecedents of the American people.

Trump's wall flies in the face of the Constitution of the United States of America when considering that the Bill of Rights - "Nowhere in the first 10 amendments to the Constitution is the word "citizen." Often it is written "The right of the people..." The Bill of Rights protects everyone, including undocumented immigrants, to exercise free speech, religion, assembly, and to be free from unlawful government interference. " and The 14th Amendment which ensures that "...nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

ITo date there are in excess of 40,000 undocumented immigrants (daily number) held in custody in US detention centres.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Explorer eaten by Cannibals

Italian explorer, Giovanni da Verrazzano, passed by Cape Fear, North Carolina, on his ship, La Dauphine, in March, 1524. He reported to his sponsor, King Francis 1 of France, that he had found the entrance to the Pacific Ocean, an error that would influence maps of North America for hundreds of years to come.

Continuing his voyage northwards along the coastline of New Jersey,Verrazzano observed natives, the Lenni Lenape or Delaware, living beside what he took to be a large lake, but was, in fact, the entrance to the Hudson River. He sailed along Long Island and entered Narragansett Bay where he met with a delegation of Wampanoag natives.

For charting the Atlantic coast of North America between the Carolinas and Newfoundland, including New York Harbour, a bridge was named after him; the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge in New York.

It's such a shame then that the explorer who had mapped out the coastline of New Jersey ended up being eaten by Caribe cannibals on one of the Lower Antilles in 1528!

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

New Jersey - The Dutch Years Part One

For tens of thousands of years the ancestors of the Delaware natives of New Jersey lived an itinerant way of life, following migratory herds of prey, fishing in fresh rivers and along the eastern coastline, and setting up bark-sided houses that could be easily dismantled and carried to the next location. Small-scale agriculture and their nomadic way of life saw the Delaware benefit from fertile soil, plentiful wildlife and abundant vegetation.

Enter the Dutch!

Henry Hudson in 1609. He sailed for the Dutch East India Company, exploring the East Coast including Delaware, Raritan, New York Bays and the Hudson River. Then came Adriaen Block who mapped out the coastline along Delaware, New Jersey, Long Island and New England. He gave this region the name New Netherlands. Block Island, Rhode Island is named after him.

Factorij or trading posts were being established at Commipaw, Hopoghan Hackingh (Hoboken) and Arresick (Paulus Hook) from 1617 onwards.

Small outposts were sprouting up in and around the Delaware River from 1624 to cater for a burgeoning fur trade. Cornelius Jacobsen Mey, after whom Cape May is named, arrived with thirty families who were to colonise the area and establish the province of New Netherland. Walloon settlers who had arrived on Nut (Governor's) Island were sent to a fort on an island previously called Murderer's island, renamed Prince's Island in honour of Prince William of Orange and now called Burlington Island. The settlement, Fort Wilhelmus, was located in the South or Delaware River. This would see the first European settlement in New Jersey.

Across the Hudson (Noorte) River from New Amsterdam and, on the banks of Upper New York Bay, the next permanent colony was a patroonship, a large parcel of land granted by the West India Company to a Dutchman called Micheal Pauw. This was in 1630 and was bought for a ridiculous sum that I outlined in my previous blog: The Price of Hudson County.

Micheal Pauw was a burgermeester from Amsterdam and a director of the West India Company. It was in his vanity that Pauw latinised his surname and called the settlement Pavonia. Translated, this

means peacock - rather an apt word!! Bought from the Lenape, this was the territory of the Turtle Clan or Unami.

Pauw's holdings eventually included Staten Isand, Bergen Point (which included eight miles of shoreline on both Hudson and Hackensack Rivers), Bergen Neck and Paulus Hook (including a ferry). Quite a hand to hold if you'd been playing Monopoly! His downfall came when he established a plantation, worked by African slaves, but failed to fulfil the company's condition of having at least fifty permanent settlers. Pauw was required to resell his acquisitions back to the West India Company.

Part Two - Anglo-Dutch squabbling!

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

New Jersey is Born

How does a huge area of land in Eastern America come to be named after a tiny island off the coast of England and France? Here begins the history...

In the 17th century, the Dutch West India Company found that it needed patrons to invest in their ventures in the New World. To those ends it introduced Patroonships, a form of plantation ownership, where wealthy men in Amsterdam in Holland were encouraged to take on areas of wilderness in New Netherland with the proviso that they would send at least fifty colonists to settle there.

One of the best locations was snapped up in 1630 by Michael Pauw, who named his Patroonship, 'Pavonia', after his own Latinised surname. It was located along the west bank shores of the Noorte (Hudson) and Hackensack Rivers and sat opposite Manhattan Island.

Unfortunately, this Patroonship was a dismal failure and Pauw swiftly sold it back to the West India Company. The Company set about resettling Pavonia and in 1633, commissioned the building of a homestead for one of its superintendents, Jan Evertsz Bout. The spit of land on which the house was built was known as Jan de Lacher's Hoeck or Jan, the Laughter's Point after his jocular nature. His homestead was the beginnings of present-day Communipaw, named after the Lenape gamunkpeauke, meaning the 'landing place on the other side of the river'. Bergen was a factorij or trading post for this colony. Plantations, worked by enslaved Africans, spread out across the lowlands between the shoreline and the hills.

A second bouwerie (home farm) was established in 1634, for Bout's replacement, Cornelis Hendriksen Van Voorst, at Ahasimus, the Lenape for 'Crow's Marsh.' Voorst's descendants would play a prominent role in the development of Jersey City.

Dutchman Abraham Isaac Planck was given a land grant for Paulus Hook on May 1, 1638. A small farmstead was set up at Kewan Punt. In Hobuk (Hoboken), the leasehold of Aert Van Putten saw the founding of North America's first brewery.

Further small settlements were established throughout Pavonia, securing a foothold on the west bank of the Noorte River and giving the West India Company strategic control over the trading posts for settlers and natives who dealt in valuable beaver pelts.

As the Swedish and the English move in, can the Dutch survive? Read what happens next time.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

How was New York City born?

Positioned neatly in the confluence between two rivers; the Hudson River and the East River, Manhattan Island was a natural location for explorers to land and for traders to set up trading

posts.

The first settlers to arrive in the wake of explorers, Henry Hudson and Adriaen Block, were the Dutch. They settled in 1623 on Nut Island (now Governor's Island) until, needing more pasture and

water for themselves and their cattle, they moved onto Lower Manhattan in 1625.

The West India Company laid down an organised and efficient set of instructions for the care and protection of the land and people of its new colony. Unfortunately, the first provisional

Governor of the new colony was Willem Verhulst, a troublesome man, who misappropriated funds and caused strife with the local natives, who had been very supportive to the new settlers. The colonists

demanded his removal from office and the post of Director General was then given to Peter Minuit.

In early 1626, news arrived in New Amsterdam that Dutch settlers at Fort Orange (Albany) had been massacred by hostile Mohawk natives. Minuit was a man of practical vision and immediately saw that

the geographic location of New Amsterdam had many advantages. It was on the tip of an island, surrounded by water, with far-reaching views across the Bay - here was a great place for a defensive

fort. The settlement's deep harbour was connected to Upper Bay and then to the Atlantic and was perfect for large trading vessels making the journey to and from Europe. There were flatlands for

farming, freshwater streams and the sea for fish, forests full of wildlife; beaver, wolves, deer, black bear, mountain lions and game and it was a place where fur-trapping natives came from far and

wide to trade.

Fur traders were in their element. In Europe, the fashion for high crowned hats created a lucrative market for beaver skins. The pelt which lay beneath the top layer of their fur was used in

making felt, a must-have for the status conscious in all walks of life from Puritans to nobility.

In 1626, Peter Minuit purchased the island of Manhattan from the local natives, the Lenni Lenape, for 60 Dutch Guilders or $24. Of course, the natives had no idea of land-ownership. Property deals

to them meant giving permission for those lands to be used by the newcomers in exchange for knives, blankets, kettles and other useful implements. They also looked to the Europeans as military allies

against their own enemies.

So, why does the Seal of New York City have the date of 1625 and bear the name of New York when it was still Dutch at that time and called New Amsterdam?

More next time...

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

New Jersey - the invasion continues

Early in the game, the Dutch recognised the huge potential that lay in the New World: an endless source of luxurious furs; vital timber supplies at a time when Europe needed wood for fighting wars, shipbuilding, and housing; and a key geographical position for the route to the fabulous Orient and its riches.

Although the Dutch were not a 'colonising' nation like the English, the Spanish and the French, they nevertheless saw the advantage in having a 'presence' in the Americas. To those ends the Dutch West India Company settled their 'employees' in strategic areas around the eastern coastline so as to command the best vantage points. With the island of Manhattan under their flag, they gained a deep, natural harbour in New York Bay, the East and Hudson Rivers afforded ease of transport to the innermost reaches of the surrounding wilderness, as well as being the means by which the natives brought along and sold their perfectly trapped pelts, Pavonia (New Jersey) forests supported all manner of wildlife, soil was rich enough to grow crops and the indigenous natives had been mainly supportive.

For a while the Dutch sat happily enough in New Netherland, the vast expanse of territory stretching from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod, with their Company hauling in profits hand over fist. But this wasn't to last. Their grip on the southern area of their territory was compromised by the destruction of Zwaanendael, a patroonship belonging to Samuel Blommaert and Samuel Godijn by local natives in 1631. Apart from Fort Nassau and its small colony, settlement along the Zuyd (Delaware) River was limited, therefore when Peter Minuit - the man who had been instrumental in purchasing Manhattan Island for the Dutch and was later fired by them- obtained a commission from the Swedish Queen to sail to America. Minuit knew of the Dutch achilles heel and captained his ship, Kalmar Nyckel, accompanied by the Fogel Grip, up the Zuyd River to a spot on the Minquas Kill tributary. He established the colony of Fort Christina, named for the Swedish sovereign, on the southern banks of Godyn's Bay (Delaware Bay), named for Samuel Godijn of Zwaanendael.

For the next 17 years the Dutch and the Swedish were at each other's throats, vying for land and its rich commodities. Pieter Stuyvesant would eventually end up taking the Fort and claim the surrounding territory for the Dutch in 1655.

Before leaving to settle in the Americas, the prospective Swedish colonists had had the presence of mind to commandeer Finnish woodsmen to accompany them to the New World. In addition to the farming methods the Finns employed to enrich their soil for crops - cutting down forest and burning the timber for nutrients, they had a unique method of cabin-building, which prevails to this day as the iconic American log-cabin.

Next time the English make their move ...

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

A Homage to July 4th and American Independence

Throughout the many years of research for my book, The Love of Money, I was constantly struck by historically documented tales of the tenacity and ingenuity of the European settlers who colonized the East Coast of America and how that spirit to survive and flourish in a hostile New World imbued their descendants with a steely determination to rid themselves of foreign tyranny and injustice.

In Philadelphia on January 10th, 1776, a fellow countryman of mine published an anonymous pamphlet. It was tantamount to a treasonable act at the time as it called for Americans to rise up against

the oppression of the British King George and his punitive laws and taxations. Its working title had been Plain Truth, but its published name was Common Sense and it was written by Englishman, Thomas

Paine. It achieved extraordinary sales reaching most of America's then 2.5 million colonists. Paine maintained his anonymity until March 30th, 1776. He donated all his royalties from Common Sense to

George Washington's Continental Army.

The sentiments and passion in the pamphlet captured the hearts and imaginations of a newly cohesive people and inspired the Thirteen Colonies to declare their position and fight for independence in

the Summer of 1776.

On July 4th, 1776, the Continental Congress approved Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence from Great Britain. This day was described by John Adams as 'the most memorable epoch in the

history of America.'

Adams also stated that this first day of debate of this Declaration 'will be forever celebrated in America.' 'It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God

Almighty,' he wrote. 'It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illumination, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time

forward, forevermore.'

His prediction could not have been more accurate.

John Hancock, President of the Congress, declared after scrawling his signature rather boldly across the document, 'There, I guess King George will be able to read that.'

Ben Franklin reflected, with a shot of humour, that, 'Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.'

On September 9th, 1776, the nation's name changed from the United Congress to the United States.

I would like to pay my respects to the bravery and courage of those Founding Fathers.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Native American Wars in New Jersey

The area of North America that now encompasses New Jersey, Manhattan, New York State, Long Island, Coney Island, Staten Island, parts of Delaware, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and Rhode Island was collectively known in the early part of the 17th century as New Netherland. It was an enormous chunk of land and was under the control of a single company, the Dutch West India Company. The New World settlement of New Netherland was run as a business and enterprises there had to be profitable. The post of Director-General would be recognised today as the CEO of a major global corporation. His governance was reinforced by an army of soldiers.

New Netherland, though, was not particularly profitable. Defence of the colonies was costly and non-effective and so land 'purchase' agreements were entered into with the local natives.There would be common use of lands, friendly relations and mutual protection. In 1639, Governor Kieft decided that, as the Dutch had 'bought' the land from the natives, extracting 'tribute' from the natives was an excellent fund-raiser and, ignoring long-term settlers' advice, he imposed his plan. Tribal leaders rejected it outright and this set Kieft on a headlong clash with local tribes.

Seizing on a rumour of natives stealing pigs from Dutch farmer David de Vries, Kieft ordered soldiers to raid a Raritan village on Staten Island. When the natives responded by burning down De Vries' farmhouse and killing four farm hands, Kieft offered a bounty payment of ten fathoms of wampum to rival tribes for each head of a Raritan native. It was later learned that the hogs had, in fact, been stolen by other Dutch settlers!

In 1641, Claes Swits, a Dutch colonist and owner of a popular public house in Deutel (Turtle) Bay, Manhattan, was beheaded by one of his customers, a 27 year-old Wappinger native, in revenge for the death of his uncle by white colonists. This incident reinforced Kieft's determination to wage war against the natives of New Netherland in order to subjugate the tribes and to levy tribute.

In 1643, natives from the Wappinger Confederacy were fleeing attacks by the Mahican and had sought out protection from the Dutch at Fort Amsterdam. The refugees set up camps at Communipaw (Jersey City) and Corlaer's Hook (Lower Manhattan). They had no idea that there was a price on their heads. Kieft responded by sending 129 soldiers to kill the natives as they slept. One hundred and twenty innocent natives, including women and children, were murdered. This savage event has become known as the Pavonia Massacre.

In retaliation for this atrocity, a force of 1,500 natives invaded the New Netherlands territory destroying homesteads, villages and settlements that had been two decades in the making. Among the dead was Anne Hutchinson, a notable dissident preacher, who had been cast out from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, for her anti-Puritan views. It is also unclear as to whether Jonas Bronck, after whom the Bronx is named was a fatal casualty of this uprising. A few months later, Dutch troops responded by killing 500 Weckquaesgeek.

Kieft's War against the natives flew against all the advice from his Council of Twelve Men and, when the war eventually came to an end with a truce and peace treaty in 1645, Kieft was recalled to the Provinces of Holland to answer for his actions. He died in a shipwreck en route in 1647.

His successor was Pieter Stuyvesant.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Native American New Jersey

Before I address the story of how the English managed to take New Netherlands from the Dutch and claim sovereignty in America, I'd first like to mention the other nation that lived on these lands before any Europeans settled.

I mean, of course, Native Americans. My first knowledge of such a people came when I watched a sixties TV programme called the Lone Ranger. Being English I believed that 'Indians' came from the subcontinent of India in the East. This image of an American native was one that was reinforced by subsequent films in the 'Cowboy and Indian' genre which depicted the natives as barbaric heathens intent on massacring the white man. I know understand a little more about this conflict.

Firstly, the Dutch. A hardy seafaring nation who had raised lands and great cities by draining below-sea level countryside, a creative and innovative people responsible for many great works of art, architecture and who encouraged philosophical literature. They had a business-like mentality that saw commerce and trading as a priority and with this came the acquisitive nature of the Dutch.When explorers searching for the elusive Northwest Passage to the riches of the Orient accidentally discovered the Americas it provided an irresistible trading opportunity for Dutch merchants.

When the first colonists and Governors of the West India Company made tentative inroads into the wilds of the eastern seaboard of America and attempted to settle, they encountered failure of crops, famine, Ice Age temperatures and fatal illnesses. It was the natives who helped to ease some of their misfortunes.

Secondly, Native Americans. The story of how the Dutchman, Peter Minuit, bought Manhattan for $24 is well known and is a tale of modern day incredulity. But when we come to understand that the indigenous population had no idea of land 'ownership', then we begin to see why conflict was inevitable. Trade agreements, familial and societal structures were misconstrued and misunderstood by both sides and the lack of a common language further frustrated the situation.

Living a nomadic life, natives revered the seasons of nature, following migratory routes of the animals they hunted for food and clothing, establishing temporary camps to grow their crops and then after the harvest move on to fresh fields to save the soil from overuse. Their love and worship of all things in nature is underscored by their naming of places and rivers that still exist today: Schenectady "beyond the pines"; Poughkeepsie "reed-covered lodge by the little-water place"; Hackensack "stony ground"; Hoboken "land of tobacco pipe"; Manhattan "island of many hills"; Amagansett, "the fishing place"; Connecticut "at the long, tidal river".

It's little wonder that relations between two such differing cultures sank into bloody, relentless war.

In my next blog - the wars: Pavonia Massacre in 1643, Kieft's War 1643-45, and the Peach Tree War in 1655.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Thanksgiving Part One

It wasn't a great journey - 3,000 miles in a leaky, wooden galleon, at the mercy of all the elements: thunderstorms, howling gales, freezing snowstorms, maggoty meat, weevil-infested biscuits, soured beer, no water, all within an atmosphere of stinking animal ordure, human vomit and Death on constant call with his life-ending scythe.

Then, imagine stepping onto stable ground, the churning sea behind you, ahead green meadows, flowers, fully clothed trees, the sweet smell of brine-less air and tinkling streams of pure mountain water.

Yes, this is your first first day in the New World. Here you can worship your God without fear of persecution, you can build a cabin to house your growing family, till

the land and grow your grain and vegetables and live in freedom and happiness..

Paradise Arrived!

No, not really!

Where's your first meal coming from? Where is your shelter for the first night? What do you do with your worldly possessions? Your seed crops are spoiled from exposure to seawater on board ship. What plants are poisonous? What wild animals are lurking in the forests ready to kill you?

Henry Hudson described the island of Manhattan as “The land is the finest for cultivation that I have ever in my life set foot upon, and it also abounds in trees of every description.”

This account, along with glowing reports from the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, had enticed all manner of people to the New World: Pilgrims, Puritans and

Calvinists, who sought religious freedom of worship and settlers, who wanted a life away from the strictures of poverty, punitive laws, robbing nobles and European wars.

The truth of this new land, though, was not what the colonists had expected - it was an alien territory of disease, the unbearable cold of a mini Ice Age, no food and very little shelter. There was, however, God's love, hope, a gritty determination to succeed and the local natives, the Wampanoag.

The Mayflower's Pilgrims landed on December 16th, 1620 and set up home in a deserted Wampanoag village, Patuxet. It had been abandoned four years earlier after an outbreak of the plague, brought by earlier Europeans, had wiped out two-thirds of the tribe in the region, which, pre-pestilence, had numbered between 50,000 and 100,000.

Although the Wampanoag had noted the arrival of strangers, they had not regarded the newcomers as a warlike threat as they were accompanied by woman and children. The natives observed them through their first winter, but kept their distance.

On March 16th, 1621, Samoset, a member of the Moneghan tribe from Maine, visited Patuxet. He returned the following day accompanied by a Wampanoag native called Tisquantum or Squanto. It was this kindly man who showed the Pilgrims how to plant corn, where and how to fish and what nuts and berries were safe to eat. That same month the Pilgrims and Ousamequin or Massasoit, the Pokanoket Wampanoag Chief, agreed a treaty of mutual protection.

In the Autumn of 1621, the Pilgrims harvested their first crop, and it was a fine yield. The Pilgrims sent four men 'on fowling' and, according to an account by Pilgrim Edward Winslow, one of only two sources of this historical event, they used guns to capture their prey. On hearing the gunfire, Massasoit believed his settler friends were under attack and showed up at Patuxet ready to give support.

The natives were invited to join in the harvest festivities, but there were 90 natives and there wasn't enough food for all. Massasoit sent his men out to hunt and

they brought back five deer which they presented to William Bradford, the English leader.

The ensuing feast lasted for three days. There was venison, seafood, water-fowl, maize bread, pumpkin, squashes of all description and possibly 'fowl' or turkey.

How did this small feast of sharing and giving thanks at Patuxet become Thanksgiving, one of the greatest annual events in American history? See Part Two of 'Why Give

Thanks?'

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Thanksgiving Part Two

Giving thanks to God, whatever the religion or belief system, has been part of every culture since time immemorial: for health, for victory over rivals and for plentiful harvests. Special dates are set for these Festivals and most are celebrated on an annual basis.

The tradition of Thanksgiving in the United States has its roots in English history.

In 1536, during the reign of King Henry Ⅷ, there were 95 Church holidays and 52 Sundays, when no work was allowed and attending Church services was mandatory. After the Reformation, this number

was reduced to 27, with some Puritans wishing to eliminate Christmas and Easter festivities, too!

The 'Holy Days' became Days of Fasting and Days of Thanksgiving. Fasting Days were to mark disasters and threats and Thanksgiving Days to celebrate special blessings coming from God.

Puritans and Pilgrims who emigrated from England took these traditions with them to New England. Pilgrim holidays in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1621 and 1623 and the Puritan holiday in Boston in 1631 are among the first Thanksgiving Days recognised in American history.

Harvest festivals did not become an annual affair in New England until the late 1660's, when Dutch-held territories in the New World were seized by the English. Thanksgiving proclamations were declared by both State and Church until after the American Revolution and were invariably on differing dates. An annual nationwide Thanksgiving date was announced by George Washington in 1789 and it was to be known as “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favours of Almighty God.”

In 1863, President Lincoln proclaimed that the last Thursday in November was to be a day when all Americans, from Northern and Southern States, joined together in unity to celebrate Thanksgiving. Unfortunately the Confederacy refused to recognise Lincoln's authority and it was not implemented until the Reconstruction in the 1870's.

On 26th December 1941, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed a joint resolution in Congress citing the fourth Thursday In November as the national Thanksgiving Day.

It is always with a sense of envy that I watch reports of Americans celebrating this very important festival. People travel for hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles to be reunited with their relatives on this special day and reaffirm their love and care for one another and their country.

In England, we do not have any comparable occasion. The Scots have Burn's Night, the Irish celebrate St.Patrick's Day and the Welsh have St. David. St. George's Day, honouring our English Saint, is a lukewarm, recently revived attempt at recognising England, but somehow it only seems to be drunks and fanatics who enjoy it, nor do our harvest festivals have quite the importance or relevance they once had with the advent of supermarkets and all-year-round imported foodstuffs. In a way it's very sad and not having our Day of Thanksgiving doesn't allow us to embrace our past and acknowledge those that built our country.

America – your ancestors survived unimaginable hardships in crossing the Atlantic, starvation, hostile environments, adversities we can only wonder at, but your adventurous spirit and sense of nationality prevailed - you should always give thanks for that!

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Wall Street - Manhattan

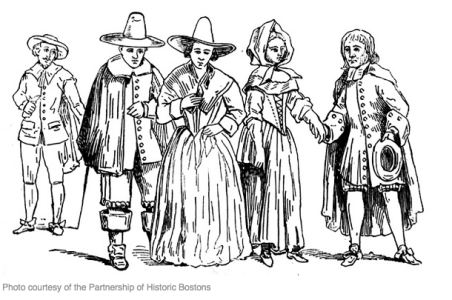

A line drawing of a wooden palisade beside which 17th Century merchants, dressed in breeches, doublets and plumed hats, discussed trading affairs struck such a chord in my imagination that it would, thirteen years later, be the basis of a book, The Love of Money, just published, about the early days of New York City and the settlers who would become the founders of the American nation we know today.

It came as quite a surprise to me that the Dutch were the first real European influence in the growth of New York. As an Englishwoman my education was heavily English-biased as you would expect, and, in doing the research for my novel, I was constantly surprised by the ingenuity, tenacity and tolerance of the Dutch settlers. They showed fortitude and bravery in the face of overwhelming obstacles - a perilous 3,000 mile sea crossing, disease, famine, hostile natives and the same warring European nations, but in the New world.

Despite this, they set about working for the West India Company, without complaint at the uncivilised working conditions, the long hours and paltry wages.Did you know that Wall Street, New York City

was named after a real wall?

In 1652, when a new war broke out in Europe between England and Holland, fear of attacks from the English, whose territory lay on three sides of the Dutch colony, pushed the Governor of the colony,

Pieter Stuyvesant, to address the issue of defence against hostilities. Stuyvesant called together the burgomasters and magistrates of the colony and set about discussing the building an effective

defence for the town, not only for its citizens, but also for Dutch settlers, who had farms and homesteads outside the town’s boundaries.

In March 1653, it was decided that the woefully inadequate Fort of New Amsterdam was to have a makeover, a night watch would be set up and that the newly incorporated city should be walled and have a

‘wall street’. The cost to the Treasury was 4-5,0000 guilders, the cost being offset by tax levies on the Dutch according to the value of their estates.

The contract price for the wall alone was 3,166 guilders or $2,166.

Constructed of pales, 12 feet high, 18 inches in girth and with sharp points on top, the wall measured 180 rods (990 yards) beginning at the East River and ending at the North or Hudson River. This

is a surprisingly short distance given that this spanned the entire width of Manhattan. Levelling and landfill have added extra girth since then. The wall was finished on 1st May 1653, the entire

project taking less than two months to complete.

Since I began writing my novel in 2001 and researching this period in history, a significant event in Manhattan focussed the entire world’s attention on this tiny section of New York and, since then,

surprising new information has surfaced about its early days.

I still find myself marvelling at how the response to a possible aggressor nearly four hundred years ago and the decisions taken to address have shaped the way the world is today.

I shall be sharing so many more interesting and varied facts about New Amsterdam, New York and the New World in future blogs.

My book, The Love of Money, is set against a backdrop of slavery, pirates, Native Americans and the colonization of the New World by feuding European nations. It charts the lives of three

different young men brought together by murder, rape, ideals and revenge.

Trading is the backbone of survival and the New World offers untold wealth, but that also brings with it greed and treachery.

Pioneering settlers sought freedom from religious persecution, European wars, poverty and social repression. A new beginning in the New World beckoned.

Pre-Wall Street this story is about the settlement of New Amsterdam and the beginnings of New York.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Who gave his name to The Bronx?

The names of villages, towns and cities can tell so much about their history.

In the UK, we are taught from an early age, to identify and understand the origins and meanings of the names of our counties, towns, villages and cities. Mostly, they come from Anglo Saxon, Roman, Norman or Viking roots, so we know that the suffixes ‘ham’ means a village, ‘ford’ a shallow river crossing, ‘wick’ a hamlet, ‘caster/chester’ a Roman camp, ‘ton’ a farmstead or manor and so on.

While researching the names and origins of towns and villages in the New World for my book, The Love of Money, a novel set in 1640’s New Amsterdam, I became intrigued by the names that settlers had given to their colonies, towns and landmarks.

The Bronx is a case in point. Jonas Bronck was a Scandinavian-born immigrant who arrived in New Netherland in 1639. Initially, he leased land north of New Amsterdam from the West India Company and bought further tracts of land from local tribes. He ended up with 500 acres on which he grew tobacco, farmed cattle and forged good trading relations with the Lenape natives.

Jonas Bronck called his homestead Emaus, a New Testament reference to a place called Emmaus, where Jesus appeared before two of his followers after his resurrection. Bronck’s farm was bounded by a freshwater river that the Lenape called Aquehung to the east and a small river running through the centre of Manhattan Island that later became known as the Harlem River to the west.

The Aquehung became known locally as “Bronck’s river,” and was eventually called the Bronx River.

The definite article in name, The Bronx, is possibly the possessive form of the Bronck family, as in ‘belonging to The Broncks,’, but it might also be attributed to the style of referring to the

rivers of the area.

So, a large area of a major city was named after a Swedish farmer who died nearly four hundred years ago. If only he’d known….

I would like to thank the Bowery Boys, http://theboweryboys.blogspot.co.uk/, for their excellent blogs - a treasure trove of New York history!

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Which NYC Borough is twinned with London Borough of Lambeth?

In my last blog, ‘Who gave his name to the Bronx?’, I wrote about Jonas Bronck, a Scandinavian-born immigrant who settled in New Netherland, a colonial province claimed by the Dutch in 1639

covering territories from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod, including Manhattan Island, parts of New Jersey, Delaware and Connecticut and small outposts in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

In 1646, the Dutch West India Company granted a parish charter to the Dutch-settled town of Breuckelen, naming it for the Dutch town of Breukelen in the province of Utrecht in the Netherlands.

Breukelen translates as ‘Broken Land,’ an apt description of the waterlogged countryside surrounding Utrecht, which lies between Rotterdam and Amsterdam in Holland. The small town of Breuckelen sat

along the East River shoreline of Long Island (Lange Eilandt).

Cornelius Dircksen Hoogland was a Dutch farmer and innkeeper who, in the early 1630’s, owned 16 acres of land that stretched along the Manhattan Island coastline from Pearl Street northeastwards. He soon realised that there was a need for transport across the East River from New Amsterdam to Breuckelen for settlers, traders and natives and that he could maintain a skeleton ferry service in addition to providing accommodation for those merchants and travellers. Cornelius established his new business at the narrowest stretch of the river, a route historically used by the Native American tribe the Lenni Lenape. As he was primarily a farmer, passengers were required to blow through a shell horn that hung from a tree beside the ferry site to summon him. The canoe carried two people in addition to the ferryman and cost three stuyvers, (the equivalent of 6 cents at the time or 0.8 cents in current value). The fare was paid using wampum - a string of either nine purple beads or eighteen white beads. Corneluis employed a man to operate the service from the Breuckelen side. It often took close to an hour to cross the turbulent East River.

In 1642, Cornelius upgraded his service, using larger sailing vessels and a regular timetable of crossings, from 5am to 8 pm, approximating sunrise and sunset, and now owned 33 acres of land near Breuckelen. A year later he sold the Breuckelen landing to Willem Jansen for 2,300 guilders, a decision he later regretted when a rival tavern was established on Jansen’s land.

In 1667, at the end of the second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch handed the territories of New Netherland to the English in exchange for Suriname, a country on the north-eastern coast of South America. Breuckelen was anglicized to Brooklyn. Brooklyn’s Dutch provenance continues still with its motto, ‘Eendraght Maeckt Maght’, which, translated from Dutch, means ‘In Unity, There Is Strength’ and was originally the motto of the first United Dutch Republic in Europe founded in 1581.

Later in its history, Brooklyn ranked as the third most populous city in America during the 19th century. In 1883, ‘The New Colossus’, a poem by Emma Lazarus, referred to New York Harbour as ‘the air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame’. This ‘twin’ status was underscored by the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge in the same year. But as the bridge offered a quicker, safer and cheaper means of crossing the East River, the ferry service fell into decline and eventually closed for good in 1924.

These days Brooklyn’s twin cities are farther afield: Anzio, Lazio in Italy (1990), Besiktas, Istanbul Province in Turkey (2005), Leopoldstadt, Vienna in Austria (2007) and the London Borough of

Lambeth in London.

So, from its humble beginnings as a nostalgic reminder for Dutch settlers in the 17th Century, it has grown into a multi-national, multi-cultural Borough of New York City with over 2.6 million people.

My novel, The Love of Money, has further mentions of Brooklyn in the 17th Century.

Read the first 50 pages of The Love of Money for Free!

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Who am I?

What do all these major geographical landmarks have in common?

A powerful river, a city in New York, a small county in New Jersey, a bridge linking Spuyten Duyvil in the Bronx and Inwood in Manhattan, an enormous bay - the second largest bay in the world after the Bay of Bengal - and a Canadian strait connecting that bay to the Atlantic Ocean.

The answer is navigator, explorer and ship’s Commander, Henry Hudson.

It took this Englishman to claim Manhattan Island, the jewel in the crown of the New World, for the Dutch in September 1609.

Henry Hudson was born in London, England, during the mid-to-late 1560’s. His family were wealthy merchants and his grandfather, also Henry Hudson, was a founding member of the Merchant Adventurers, a trading company which received a Royal Charter from King Edward in 1553, and which became known as the Muscovy Company in 1555.

Hudson’s privileged background would have seen him educated in cartography, navigation, mathematics and astronomy, all subjects that drew him towards sailing and exploration. A headstrong, courageous, bewhiskered man with dark hair and eyes, he was married to a lady called Katherine and had three sons John, Richard and Oliver.

Since the discovery of the riches of the Orient: Indian and Chinese silk, spices, precious gemstones, porcelain and much more, competition to find the quickest route to Cathay was intense. European nations fell over themselves plotting and scouring maps, investing heavily in doubtful ventures: monarchs, merchants and governments handed over substantial amounts of money to trading companies in order to become even wealthier and more powerful.

The quest to find the coveted Northeast Passage, a northerly route that would carve a pathway through to the Far East, was one fraught with danger, skulduggery and murder. The theory behind the a possible passage was that there existed a seaway that ran above the Artic Circle eastwards and ended in China, its access only possible during three summer months when the sun melted the northern ice packs.

Henry Hudson would attempt four of these explorative ventures on behalf of merchant companies and, in doing so, would immortalise his name.

Climactic conditions during the 17th Century were brutal. Europe and America were in the throes of a Little Ice Age that had begun in the 13th Century, bringing winters so severe that rivers froze, frost fairs were held on the River Thames in London, encroaching glaciers destroyed farms and villages in Switzerland, the freezing winter of 1607-08 claimed the lives of excessive numbers of settlers and natives in Maine and in Jamestown, Virginia extreme frost was reported and Samuel de Champlain recalled bearing ice along the shores of Lake Superior in June 1608.

So, not only was the quest for the Northeast Passage one of national competition, laden with treachery and greed, it was also set against a backdrop of sub zero temperatures, impenetrable pack ice, unrelenting blizzards, frostbite and death.

The London Muscovy Company commissioned Hudson’s services and on May 1st, 1607, he captained the 80-ton ship, Hopewell, with ten crewmen and a ship’s boy. By June, Hudson had reached Greenland and travelled northwards along its coast, across the Arctic Circle and a month later entered what Hudson called, ‘Whales Bay’. Shortly after, he met with an impenetrable wall of ice and returned to Tilbury Hope, England, in September 1607.

His next trek was funded by the London East India and Muscovy Companies in 1608. Again, Hudson was Commander of Hopewell, but this time he would follow an easterly route sailing above Russia. He sailed in April, but finding his path blocked by ice packs he turned around and landed back in Gravesend, Kent in August.

In 1609, Hudson he accepted a commission from the Dutch East India Company to once again find an easterly passage to the Indies. Leaving Amsterdam in April onHalve Maen (Half Moon), a three-mast carrack, he was thwarted once more by the inevitable barrier of ice above the Arctic Circle. This time though he did not head home, but rather took a westerly passage skirting Newfoundland and reaching Nova Scotia in late July. This decision was based on reports from previous explorers in the area, John Smith of Jamestown and Samuel de Champlain, citing Native American knowledge of a western route to Cathay.

In August he arrived at Cape Cod, foreswore exploring the entrance to Chesapeake Bay, and sailed north and found Delaware Bay. In September he reached the estuary of the North River or Muhheakunnuk (Mohican for ‘Great Waters constantly in Motion’) - now the Hudson River. After a skirmish with local natives, in which a crewmember died, Hudson travelled upriver as far as what would become Fort Orange or present day Albany. This journey would give the Dutch territorial claim to the island lying off the starboard side of Halve Maen - Manhattan Island.

Hudson would say of the island:

“The land is the finest for cultivation that I have ever in my life set foot upon, and it also abounds

in trees of every description.”

—Henry Hudson

Hudson’s voyage ended back in England in November 1609. Although he was detained by English authorities, who were upset at his working for the Dutch, his log was passed over to the Dutch Ambassador for England and handed to the Dutch East India Company officials in Amsterdam.

His final voyage in 1610 was under the English flag again. Funding from the English East India Company and the Virginia Company saw him take the helm of a new ship Discovery, with a remit to find the Northwest Passage. Rounding the southern tip of Greenland in early June he reached what is now known as the Hudson Strait and entered Hudson Bay at the beginning of August. He did not find the illusive passage to the Far East. November saw him trapped in ice in James Bay. Having survived a bleak winter on land, the crew wanted to go home, but Hudson did not. The crew mutinied and eventually Hudson, his son John and a few crewmen were forced into a small boat, with inadequate provisions for their survival, and that was the last that anyone saw of Henry Hudson. It was June 1611.

What an ignominious death for such a brave, intrepid explorer. Check out my novel, The Love of Money, for further reading on 17th century life.

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Why I wrote The Love of Money

To remember why I wrote my book, I need to think back to when I first had the idea to commit to a novel. No particular subject had gripped me and I had already started many projects that are yet to be developed.

I was casually grazing through sites on the internet which, back in 2000, were slow to load and lacking much content, when I came across details of a book about Wall Street. The book was called The Great Game by John Steele Gordon, the acclaimed business historian. I read some of the sample material and found myself drawn into a riveting history of a little lane, originally called Het Cingel, in New Amsterdam that went on to change the nature of trading and commerce forever.

I bought the book, read to page 192, and then saw the picture that was to capture my imagination. It was a simple, woodcut illustration depicting a primitive palisade beside which two men in doublets, boots and breeches stood discussing the merits of a high wall. Above the two chatting men was a guard, musket over one shoulder, patrolling atop the four-foot high breastwork that supported the twelve-foot pales. It was 1653 and this was newly-built Wall Street in New Amsterdam, a Dutch colonial town on the tip of Manhattan Island, that would become the foundation upon which New York was built.

One of the men had a peg-leg and was pointing at the wooden defence with his walking stick. That man, the man responsible for ordering the construction of the wall as protection for the colony against attacks by natives and foreign enemies, was Governor Pieter Stuyvesant.

I researched 17th century history and, in particular, the period of history now known as the Golden Age of Discovery, finding not only warring nations in Europe, the beginnings of global slavery, religious intolerance and conflict, pirates, Native Americans, witch hunts, racial and gender inequality, countries fighting for territorial and maritime supremacy in the New World, but also the extraordinary birth of the first truly modern nation. This was novel-writing gold!

The characters in my first novel, The Love of Money, live in that Age: they feel, smell, see and experience 17th century life. Mostly, though, my book is about how one individual can create and

influence a series of events that have far-reaching consequences for many other people. The fact that the thousands of choices, decisions and laws made during that period still affect us today is a

constant source of spine-tingling awe for me.

The surviving characters from my first novel will feature in my next and subsequent books.

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

How I survived rape, psychopaths and gangsters and wrote my first book, The Love of Money

With the list of my academic and workplace history neatly recounted under the 'About Me' heading on my Blogspot, I can now add the real story: the one that allows me to write about harrowing subjects, such as rape, murder, abuse and rejection, with authority.

Born of a schizophrenic mother, I have always been ambivalent about relationships and how much I mattered in them. I was twelve when my mother was finally carried away, restrained, quite literally, by men in white coats. There were incidents during the previous three years when I'd been drawn into her different personas – she'd fantasize about my father being dead; she'd declare, taking her hands off the steering wheel, that my deceased Grandma was driving the car; she'd leave me to be accused of stealing from a shop when Grandma hadn't turned up to pay. She had one of her worst episodes - trying to kill herself by driving into a hedge - while I was at school and I'd arrived home just as she was being taken away for 'treatment'.

My mother had never wanted me and blamed me for sentencing her to life with a man she disliked. In those days divorce was not an option. Three months later after undergoing ECT and psychotic drug treatments she returned home, a stranger to me, needing forty-two pills a day and constant monitoring.

Four years later my father moved us to London, which was wonderful, overwhelming and frightening to a naïve girl from the backwaters of Hertfordshire.

My next nightmare was at the hands of a friend of my father, Sam*, tasked to introduce me to London life. I suffered rape and humiliation at the hands of this man and his friends.

I escaped my parents' acrimonious marriage breakdown by moving in with a much older man, an alcoholic with violent moods and from a totally different background, a true East Ender, born within the sounds of Bow Bells. This was Hackney and Dalston long before they became a chic place to live, with pubs that harboured thieves and murderers, gyms that fostered the planning of crimes and council flats that held parties to celebrate successes by the likes of the Krays and the Richardsons. I was witness to a brutal gangland killing, was beaten badly myself and lived in hovels. It took me four years to return to my mother.

My next escape arrived in the form of a charming, good-looking man, well known in music industry circles, a social animal seen at every important premiere, gig and club opening. It was only when I married him and committed myself to bringing up my two sons that I discovered the back story. I lived a weird life of deceit and lies for 23 years before he finally walked out, leaving us homeless and penniless. I suffered a nervous breakdown.

Quite a life so far. But as you can see, I can talk about the disturbing world of psychopaths, mentally disturbed people and physical and mental abuse with authority. I've only skimmed over the above details – there's far, far more to come. I plan to divulge the full story of my life in future blogs.

* Not his real name

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

New Jersey - Ancient Heritage

Research for my novel, The Love of Money, was a long and involved process during which I discovered so much about the beginnings of the United States of America in the 17th century. It took me on a fascinating journey and shook up a lot of my previously ignorant notions of America.

New Jersey is one such surprise. Far from being a place of rich housewives, Italians, Jersey Shore tourists and a strong accent, this State has an ancient history as rich and as fascinating as any

in the world. An incredible heritage.

During the Jurassic Period, some 180 million years ago, New Jersey abutted North Africa. The Appalachian Mountains were a result of this head-on collision. Glaciers that formed during the Ice Age

retreated to give rise to numerous swamps, rivers and gorges, including Glacial Lake Passaic formed from the melting waters of the Wisconsin Glacier and Glacial Lake Hackensack.

Around 10,000 years ago, the original peoples of America were feisty Paleo-Indians, survivors of inhospitable terrain and harsh weather. The Lenni Lenape, immigrants from the Mississippi Valley, were

nomadic, big-game hunters, tracking wooly mammoths, giant sloths, sabre-toothed tigers and six-foot tall beavers across the icy wastelands of New Jersey an area called Scheyichbi by the Lenape. As

the climate continued to become warmer, these prehistoric animals disappeared and, in their stead, was easier prey like white-tailed deer, raccoon and bear. The Lenape fished along the shoreline of

New York Harbour using nets and fish hooks to collect clams, mussels and oysters and sea fish.

The Lenape of this region gradually became known as the Delaware. Their stone tools became more efficient and, with the advent of the bow and arrow, they began to settle in places for longer, built

oval, bark-shingled houses and practised small-scale agriculture. They grew squashes, beans, maize and tobacco and gathered nuts such as walnuts, chestnuts and beechnuts.

With venison, oysters, clams, corn, sweet potatoes and walnuts on the menu, their diet would be the envy of some of today's more discerning diners.

By the time the first European explorers arrived in the 16th century there were 8,000 to 20,000 Delaware living in parts of Delaware, New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. Life was to change

dramatically for New Jersey's Delaware natives when Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed along the New Jersey coastline in 1524.

It's an extraordinary thing to realise that, far from being a 'newly-established' country, the USA is home to one of the world's oldest peoples.

The European Invasion! Read part two in my next blog.

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Four interesting facts about New Jersey

The first American brewery was opened in Hoboken in 1642.

All New Jersey counties are classified as metropolitan areas - the only state in the USA to do so.

New Jersey is home to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island*.

Highlands, New Jersey, has the highest elevation along the entire Eastern Seaboard from Florida to Maine.

* This fact is particularly interesting as I'm sure most of us in the UK think these are in New York.

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Purchase price of Hudson County

In 1630, three Delaware natives "sold" the land of Pavonia or Hudson County to Dutch Burgermaster Michael Pauw for:

80 fathoms (146 m) of wampum,

20 fathoms (37 m) of cloth,

12 kettles,

six guns,

two blankets

one double kettle, and half a barrel of beer.

These transactions were dated July 12, and November 22, and represent the earliest known conveyance for the area.

Four years earlier, in 1626, these same Delaware natives had allegedly been responsible for 'selling' Manhattan Island to Pieter Minuit for 60 guilders before moving on to Pavonia.

Enjoy reading the first 5 chapters of The Love of Money

The Love of Money 5 chapters.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [313.1 KB]

Psychopaths – brilliant character material!

My marriage ended after 23 years, not in the way that relationships just do: corrosive boredom, disrespect or simply growing apart. One day I had a home with my husband, my two sons and four dogs,

the next I was on the street, homeless, with two sons, three dogs and no money.

At 52, and with no income, close family or savings, it was a dire situation. When the bailiff arrived to evict us, my husband took himself and his dog to live in a pretty, riverside hotel a quarter

of a mile down the lane. With all my belongings scattered about in front of my home, I watched in disbelief and shock as he ambled away from his family, with money in his pocket, a long and

successful career in the music industry, many famous friends and a published book. He didn't look back once.

I suffered a complete nervous breakdown in the weeks and months that followed. It was very tough, not only on me, but also on my two sons. I had to have a beloved, traumatised dog put to sleep.

Later, papers and letters I found among my husband's discarded belongings revealed a hidden world. A man who had lived a life of fantasy, lies and deceit; a man so completely devoid of caring,

responsibility and empathy that he could just walk away from his wife and sons without explanation. Two years later, I was granted a divorce on the grounds of his unreasonable behaviour.

So, when I create a character who is cold, uncaring, manipulative and dark, it is based on my personal experience and is the truth as I know it.

Psychopathic behaviour, as an inspiration for fictional characters, is one that could immediately conjure up images of snarling lunatics such as Hannibal Lechter and Freddie of Nightmare on Elm

Street. This is not always the case. Sometimes psychopaths can appear remarkably bland and boring, but the impact of their immoral and inhuman behaviour can be just as devastating as if they had

taken a knife to someone.